Unsustainable mortality caused by wind turbines is a major threat to North American bats. Three species in Canada have now been assessed by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) as Endangered. There are ways to reduce fatalities, but current action is inadequate in the face of severalfold increases in wind energy capacity that is already underway. Stay informed and insist that action is taken by governments and industry to address this issue.

Key Facts

(expand topic heading to learn more)

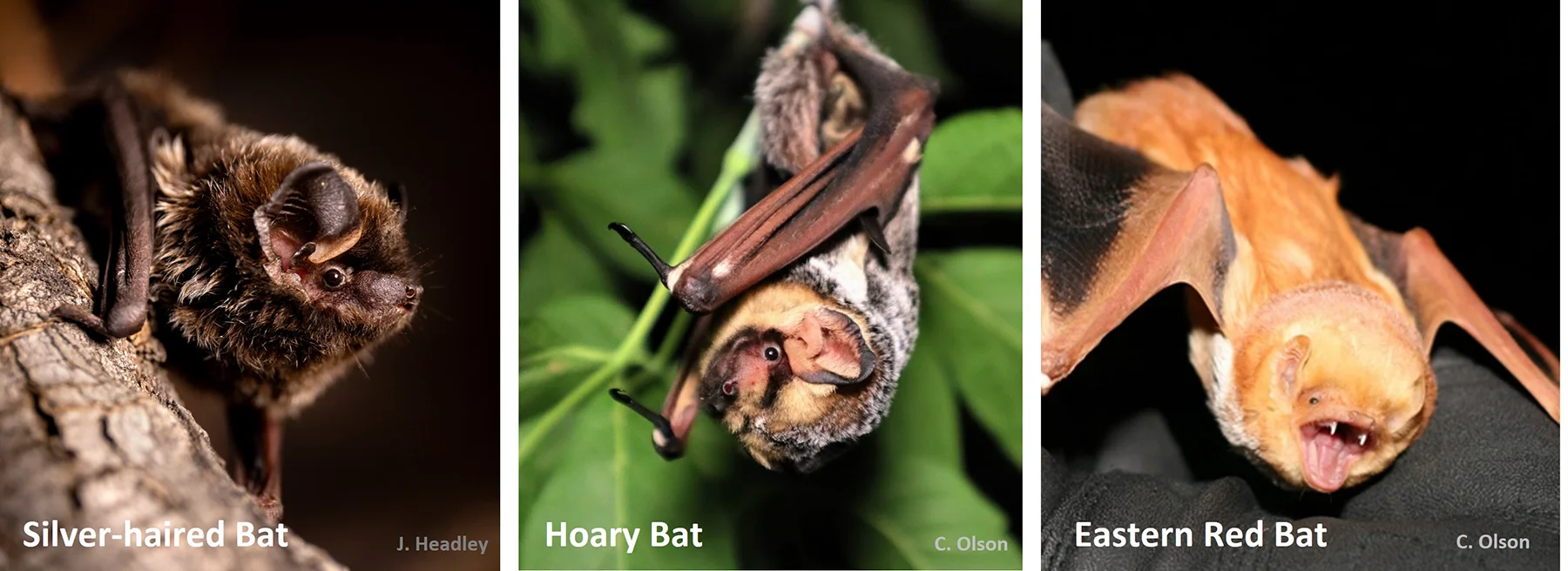

Wind farms affect a variety of wildlife in different ways. However, bats stand out as being particularly impacted by wind turbines. Across most wind farms in Canada, just two or three bat species (Hoary Bat, Silver-haired Bat and Eastern Red Bat) account for most of the wildlife fatalities. At many sites in Alberta, Hoary Bats and Silver-haired Bats account for more fatalities than all songbirds combined. Some raptors (hawks, falcons and eagles) are also impacted by wind turbines, especially species such as Ferruginous Hawks that have limited ranges in Alberta and are already at risk from human activities.

Although many different bat species have been found dead at wind turbines, three species account for most fatalities in Canada: Silver-haired Bat, Hoary Bat, and Eastern Red Bat. These species share at least three important characteristics that may help explain their susceptibility: 1) they all undergo long-distance migrations during the spring and fall, with most likely spending the winter somewhere in the United States; 2) they all roost almost exclusively in trees during the summer; and 3) they are all well adapted to fly in the open, crossing long distances in short time periods.

In Alberta, Eastern Red Bats are not found dead in large numbers because the species is near the western limits of its geographic range, and is therefore relatively uncommon in the province (and nearly all individuals that do occur here are males). Eastern Red Bat fatalities increase towards eastern North America where the species is more common. All three species are long-distance migrants (most leave Canada for the winter) and most fatalities occur during fall migration. Resident species (such as our various Myotis species) are not found dead nearly as often at wind turbines, but this situation could change depending on turbine design and siting.

Bats are only killed by wind turbines while they are flying, which only occurs at night. Also, most deaths occur at low wind speeds—when turbines produce the least power. And most deaths occur while bats are migrating south during the late summer and fall. Not operating turbines during the night, during low wind speeds, and during fall migration can greatly reduce bat fatalities, with only a modest decrease in power generation.

Bats appear to be attracted to turbines. Several hypotheses have been suggested to explain this behaviour. Although the issue has not been fully resolved, the most likely explanation is that turbines are being mistaken for tall trees. Because the three bat species most often killed at turbines all roost and fly around trees, there is good reason for bats to seek out trees on the landscape (especially when crossing the open prairies, where trees are scarce). The tendency of migratory bats to fly towards turbines is problematic because it makes it difficult to predict risk from pre-construction surveys—bats won’t be there until the turbines are built! Not surprisingly, pre-construction bat surveys often perform poorly at predicting fatality rates at wind farms.

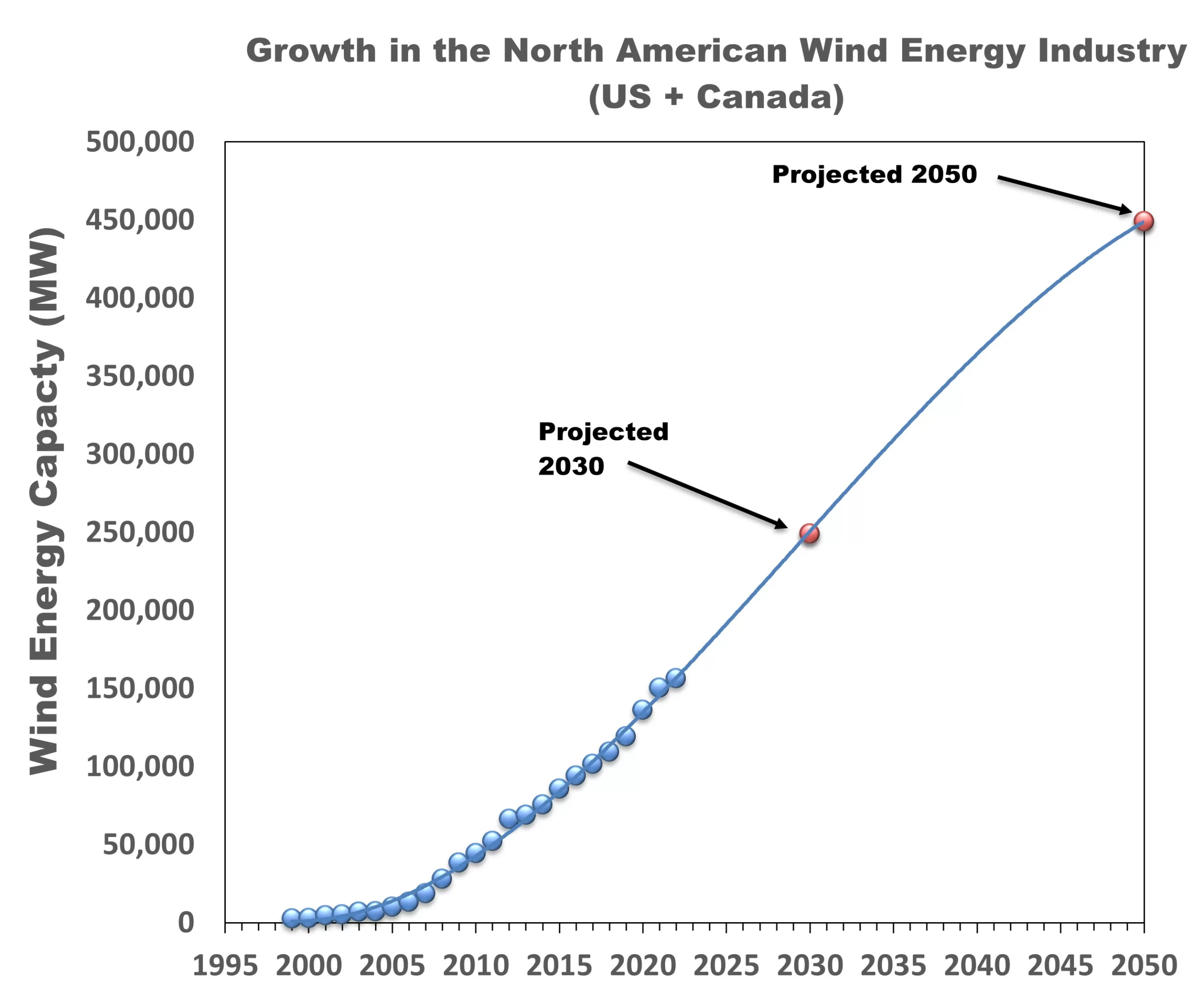

The wind energy industry is growing rapidly across North America and will soon become multiple times greater than what it was when experts first predicted precipitous declines in our migrating bat populations. This is a major concern for bats because 1) the rapid increase in the number of turbines does not leave adequate time to fully understand how populations will respond, and 2) any reductions in fatalities through the adoption of mitigation measures are quickly offset by increased fatalities from new turbines coming online.

Sources:

https://windexchange.energy.gov/maps-data/321

https://renewablesassociation.ca/by-the-numbers/

https://www.energy.gov/map-projected-growth-wind-industry-now-until-2050

There are proven methods for reducing bat fatalities, the most important being controlling when turbine blades spin. For example, turbine blades may be allowed to spin (“freewheel”) at low wind speeds, even when there is no electricity being generated. Bat fatalities could be reduced by up to 30% just by eliminating blade movement when wind is below the turbine’s cut-in speed. This results in no loss of electricity generation! Additionally, far fewer bats would be killed if wind energy companies were required to raise the turbine’s cut-in speeds (the wind speed at which rotors begin turning to generate electricity). For example, studies have shown that raising cut-in speed from 4.0 m/second to 5.5 m/second reduced fatalities by over half. Doing so does not heavily impact energy production (estimated 1-3% or less) because low wind speeds generate less power. Most energy companies are already planning on a much larger inherent range of uncertainty in wind conditions and thus energy production. Acoustic deterrents are being investigated as a potential way to reduce fatalities, but existing studies have reported mixed results, indicating that more research is needed before they are adopted for widespread use (see conservationevidence.com). However, even reducing fatalities by half may not be sufficient given the exponential growth in the number of turbines that is expected to continue over the next few decades. Unfortunately, despite there being proven methods to reduce bat fatalities, these measures remain largely voluntary and have not been required, so hundreds of thousands of bats have died each year that could potentially have been saved with only modest losses to electricity generation. More action is needed from state and provincial governments to compel adoption of proven ways to mitigate this threat.

Understanding the true scale of the problem that wind power development poses to bats requires us to consider what is happening across Alberta and North America as a whole. Each turbine in Alberta kills an average of 10.9 bats each year, and most of these fatalities have been Silver-haired Bats or Hoary Bats. There is evidence that the number of bats killed per turbine is decreasing over time, but a likely explanation for this trend is that migratory bat populations are declining (there are fewer bats remaining to be killed). There are now more than 900 turbines in Alberta and more than 77,000 across North America. In Alberta alone, annual fatalities are thought to be about 10,000 migratory bats per year, and many more of the bats that call Alberta home in the summer will die at turbines south of the border before they are able to return to Alberta the following year. Across North America, annual fatalities of migratory bats is likely in the hundreds of thousands of individuals. Bats are the longest-lived and slowest reproducing mammals for their size—their populations cannot withstand high mortality rates. This level of mortality is not believed to be sustainable and may result in the extinction of affected bat species if nothing is done.

Bats provide tremendous value to both the environment and the economy. The three species of migratory bats—Silver-haired Bat, Hoary Bat and Eastern Red Bat—are particularly adept at feeding on moths. Larval moths (cutworms, armyworms, and other caterpillars) can be major defoliators of crops and forests. These bats can eat their own body weight in insects per night, which helps make them one of the top predators of night-flying insects. Not only that, research has shown that just by being present in an area, bats create a ‘soundscape of fear‘ that helps reduce moth density, even when they are not directly consumed. It’s difficult to put a dollar value on bats, but one study estimated that bats could be worth between 3.7 to 53 billion dollars per year to the US agricultural sector alone.

But there is another great reason to protect bats—collectively, bats represent about a quarter of all mammal species worldwide. If we fail to protect this important group, there could be an irreversible loss to biodiversity on this planet. The combined impact of white-nose syndrome and wind energy puts the future of bats in the country in great peril.

What can be done?

(expand topic heading to learn more)

Wind farms don’t belong near rivers, yet many of Alberta’s wind farms continue to be placed in these areas. Bats concentrate their activity close to water. In areas with few trees (such as the open prairies), bat activity is especially concentrated along rivers. Rivers and riparian areas are used to feed, roost, access water, and are likely important migration corridors. The closer turbines are to rivers, lakes and major wetlands, the more likely they are to encounter bats. The Government of Alberta has not yet established legal minimum setbacks for wind energy projects that are biologically-relevant for bats in the province. However, a 5 km setback, as indicated in the Wildlife Siting Guidelines for Saskatchewan Wind Energy Projects, should be considered as a minimum setback from all major watercourses in Alberta until more appropriate setbacks can be established.

Migratory bats can fly over 30 km/h. A 100 m setback (the current Alberta government-established setback from the top of a valley break) could be traversed in less than 12 seconds by a bat. Clearly more meaningful setbacks are required. Even a 5 km setback could be crossed in less than 10 minutes by a bat, but this distance may at least help reduce the likelihood of a bat diverting from its original flight path.

Despite it being well known that bats concentrate their activity along rivers, wind farms in Alberta continue to be placed within or near riparian areas, which highlights the need for regulatory changes.

Bats may not want to fly over the mountains and the prairies have too few trees for roosting. The foothills are perfect habitat for bats and are a natural flyway during migration. Putting turbines along the eastern slopes of the rocky mountains is very likely to result in high bat fatalities. However, there are potentially other migratory pathways used by bats, and it is important to determine where these are before building turbines in these areas.

Even when turbines are installed in the wrong location for protecting bats, there are still simple changes that can greatly reduce bat fatalities. Bats only fly at night, so are not at risk from turbines operating during the day. They typically only fly during low wind speeds. And most fatalities occur during fall migration (although this can vary depending on location and species). In fact, bats are not even active in Alberta for about half the year. Not operating turbines during high risk period can greatly reduce fatalities—this is referred to as operational curtailment. Turbines can be equipped with bat detectors and can be programmed on an individual basis to have their blades stop turning when bats are likely present. These are referred to as smart curtailment systems and could help wind energy companies save bats while maximizing energy production (as opposed to blanket curtailment at certain wind speeds or times of day and year).

Understanding the true impact of wind power developments requires consideration of not just the environmental impacts of the development in question, but also how it contributes to impacts occurring across North America (these are referred to as cumulative impacts). All three migratory bat species impacted by wind turbines have ranges that cross provincial and national boundaries. What happens in one jurisdiction is very likely to affect migratory bat populations across the continent.

The current provincial mitigation framework does not adequately incorporate cumulative impacts (although there is mention that these will be considered during review). The original guidelines are based on activity and fatality thresholds at individual locations, but these have become inadequate given the rapid build-out of the wind energy industry across the continent.

One of the most important ways to ensure accountability is to make monitoring data public and to disclose what mitigation has been applied. Monitoring data and all reports required under the provincial wildlife directive should be publicly available as a condition of regulatory approval. These reports should detail methods, results, summarize how turbines were operated during the monitoring period, and describe any operational mitigation applied.

Research has already resulted in the discovery of multiple ways to reduce the number of bats dying at wind farms. But there is still much we do not know about bats and their interactions with wind turbines. Research into different curtailment systems and deterrents offers promising ways to reduce bat deaths, and new research may offer yet more options to address this issue. Even basic questions of bat behaviour, such as what locations they use for migration, have yet to be fully addressed. More support for research, and improved access to monitoring data from wind power facilities, are two ways to help address the threat that wind power poses to migratory bats in North America.

Selected Media Coverage

Want to learn more? We've highlighted some resources below to help you on your way.

Note: This list may not reflect the latest editions and is only a partial listing of relevant resources. Always refer to original sources.

Guidelines and Directives for Wind Power Projects Occuring in Alberta

| Title | Author or Jurisdiction | Release Date | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Government of Alberta | January 27, 2017 | These directives set a legal standard for avoiding key wildlife habitats and for mitigating impacts on wildlife for wind projects in Alberta. Among other things, the directives set minimum setbacks from sensitive habitats, establish minimum survey requirements for bats, and require proponents to report survey methods and results and to compare these results to thresholds set in the bat mitigation framework. These directives only provide minimum legal requirements in Alberta—they have not been demonstrated to be effective or adequate to prevent harm to migratory bats in the province. | |

| Government of Alberta | April 29, 2013 (revised June 19, 2013) | This framework is referenced in the Wildlife Directive for Alberta Wind Energy Projects. However, this framework is inadequate to protect bats because thresholds based on activity rates or fatalities become increasingly less likely to be exceeded when bat populations are in a state of decline. The specified thresholds were based on rates when substantially fewer turbines were in operation and when bat populations were potentially much greater than present levels. | |

| Government of Alberta | March 1, 2013 | The wildlife directive for Alberta wind energy projects requires these guidelines be followed for wind energy projects in Alberta. The section on bats mainly serves to refer users to the 'Handbook of Inventory Methods and Standard Protocols for Surveying Bats in Alberta' as well as the province's pre- and post-construction bat survey protocols. | |

Handbook of inventory Methods and Standard Protocols for Surveying Bats in Alberta | Government of Alberta | May 1, 2010 | Standard survey protocols for bats in Alberta. This document is referred to in the Sensitive Species Inventory Guidelines. Appendix 5 of this document is the 'Pre-siting and pre-construction survey protocols'. |

Post-Construction Survey Protocols for Wind and Solar Energy Projects | Government of Alberta | January 31, 2020 | This documents sets survey protocols for post-construction monitoring at Alberta wind energy facilities; an earlier version of these protocols are referenced in the Alberta Sensitive Species Inventory Guidelines. |

| Government of Alberta | NA | This database lists major projects in Alberta, including wind farms in various stages of regulatory approval or construction | |

Wildlife Siting Guidelines for Saskatchewan Wind Energy Projects | Government of Saskatchewan | September 1, 2016 | These Saskatchewan-based guidelines set a 5 km buffer (avoidance zone) from major rivers and other environmentally sensitive areas to reflect the high risk of ecological impacts if developments were to occur in these areas. Although these guidelines were not designed for Alberta, a 5 km buffer from sensitive habitats is similarly expected to result in substantial reductions in bat fatalities if applied in the province, and should be considered because of the absence of scientifically-based setbacks for Alberta wind energy projects. |

Best Management Practices for Bats in British Columbia—Chapter 8: Windpower | Government of British Columbia | February 2016 (updated 2023) | These best management practices are among the most comprehensive in Canada and should be considered in jurisdictions where more region-specific guidelines are not available (such as Alberta) |

Selected Scientific Publications Relevant to Wind Power in Alberta

Title | Comments |

|---|---|

| The authors find evidence that bats concentrate activity along select routes, and suggest that activity may be higher along the foothills and riparian areas. | |

| This is the first major trial in Alberta to demonstrate that bat fatalities can be substantially reduced (by over half) by changing cut-in speeds of wind turbines. | |

Background reading on the impacts of wind energy on bats | |

| Estimated that 888,000 bat fatalities/year occurred in the United States in 2012 at turbines comprising 51,630 megawatts of installed wind energy capacity (17.2 fatalities / megawatt) | |

Background reading on the impacts of wind energy on bats (open access) | |

| Among other topics, this article includes a depiction of changing fatality rates over time at wind farms in Alberta | |

| This article represents the first attempt to quantify the potential impacts of wind energy production on migratory bat populations (using Hoary Bats as a focal species). The authors use a combination of empirical fatality data and predicted population parameters to show that wind turbines may drastically reduce population size and increase the risk of extinction of hoary bats . | |

| Used changes in carcass abundance per monitored turbine over 7 years (2010 - 2017) in southern Ontario to evaluate potential population declines at wind farms. Found that the abundance of 4 bat species declined rapidly over 7 years, with reported declines ranging from 65% (Big Brown Bat) to 91% (Silver-haired Bats). | |

| A more comprehensive report upon which Friedenberg and Frick (2021) is based. | |

| This article presents predictions from an updated version of the population model that originally appears in Frick et al. 2017. The model incorporates different assumptions regarding buildout and adoption of mitigation measures. | |

| A simulation comparing the cost of smart curtailment systems to blanket curtailment systems for reducing bat fatalities in Alberta. | |

| Estimated that the financial cost of implmenting a curtailment system to reduce bat fatalities would only reduce power by about 0.17–1.06% (median 0.40%) at individual wind farms. |